How I actually use AI to write Ruby on Rails code

A practical workflow for coding with AI on brownfield and greenfield Rails applications. Covers context generation, layered documentation, pattern synthesis, and maintaining code quality.

Nowadays, there is a lot of noise on social media about coding with AI. It’s common to read posts from people claiming they cloned a service in hours, even though they don’t know how to code. There are also people claiming that if you’re not using a particular tool, you’re becoming obsolete—and those same people, a week later, say the same thing about a different shiny tool.

This can become overwhelming. Frustrating, even if you’re using the tools, but your results don’t come close to “building the next big thing in two hours.” Or if you expect a simple prompt to produce a complete feature. When that happens, it’s a sign you need to go outside and walk to a park.

I’ve learned to stay away from the noise and set realistic expectations for what a model like Anthropic’s Opus 4.5 can do. Here’s what actually works for me.

The real challenge with AI-generated code

Coding with AI has come a long way—from auto-completing a block of code in your IDE to scaffolding complete applications, and building features end-to-end. Models have become more intelligent, capable of solving complex problems and creating decent UI with reasonable UX.

But they have a fundamental problem: they were trained on the best-architected codebases and the messiest spaghetti code in equal measure. They lack style, favor complexity, and—most importantly—the generated code lacks your domain knowledge and your experience building software.

Don’t get me wrong, I use AI to code almost all the time now. But I’ve learned that the key is generating the right context. Without it, you’re heading into a disaster.

Coding on brownfield applications

I’ve used AI coding in large Ruby on Rails applications to fix existing features, change how they work, and add new ones. A brownfield application usually has well-defined patterns, or if it’s old enough, you can clearly see the evolution from legacy code to newer approaches.

To take advantage of AI in this kind of application, I build context in layers:

Layer 1: Technical foundation. I have the model create a synthesized document analyzing the application’s technical details—how it’s organized, which gems are used, the database, any frameworks outside Rails standard, and specific configuration settings. No domain model details, just technical architecture.

Layer 2: Pattern documentation. I built a set of technical documents that capture patterns for models, controllers, UI, API clients, testing, and API endpoints. These are synthesized files focused on existing patterns. I usually provide a set of representative files and ask the model to generalize from them.

Layer 3: Feature guides. When I need to work on a feature, existing or new, I first ask the model to generate a comprehensive guide for that feature. I point to the relevant files, provide additional guidance, and the goal is to document how the feature works, from the UI to the database, scoped to that specific feature.

Layer 4: Implementation specs. Once I have the comprehensive guides, I create a detailed spec outlining the work to be done and my expectations. I provide the feature guide along with the synthesized technical documents.

If the feature is too large, I break it into smaller specs. For most of the work, the model generates code in the right direction. But at some point, it won’t make the best decisions—what people call AI slop. Here’s where I ask the model to review the generated code, ensure it follows the patterns in the technical documents, assess its complexity, and simplify while preserving functionality. This review step is essential. Sometimes I’ll make manual changes or be more specific about which parts need adjustment and how to adjust them.

Using this flow, I’ve delivered small changes and large features to legacy applications with confidence. I don’t think there’s a need to audit every line of generated code unless the feature is on the critical path or poses a security risk.

One important note: the generated documentation needs to be updated periodically to reflect the reality of the codebase. If the docs go stale, your experience using the AI won’t be as good.

Coding on greenfield applications

Starting from a blank slate is a different experience. I’ve tried going prompt to prompt, and it works for spikes on a single feature or two—useful for proof-of-concept, where you know the code will be thrown away. But for building something real, that approach falls apart quickly.

What works for me is starting with documents before writing any code:

MVP document. I describe the application I want to build and the technology stack (Ruby on Rails, in my case). Then I let the model research similar apps, suggest features, identify what to do better, and flag which features might not be important.

Brand design document. Names, colors, logos, brand voice, and tone. This keeps the model consistent when generating UI and copy.

Implementation specs with visual mocks. From these foundation documents, I create specs for building the application. Along with each spec, I create mock visuals in HTML, CSS, and JavaScript so the model knows what I’m aiming for.

I use Claude Code for implementation. It generates plans based on the specs, and I also have it create cards on Fizzy (a task tracker) using its CLI and a custom skill. This helps me track the work across sessions.

I also maintain a set of documents describing what to do and what not to do with the code and the Rails framework. For UI, I have patterns for Hotwire, ERB, and Stimulus.js, complemented by a UI skill for working with Maquina Components (my component library).

After each implementation session, I run another skill called Rails Simplifier. It compiles patterns for models, controllers, helpers, and other layers, then analyzes the generated code for unnecessary complexity. The skill provides recommendations that the model implements before I move on.

As the application grows, I start building the same synthesized and comprehensive documents I use for brownfield applications. This keeps the model generating code consistently—or at least gives me a post-action to maintain consistency.

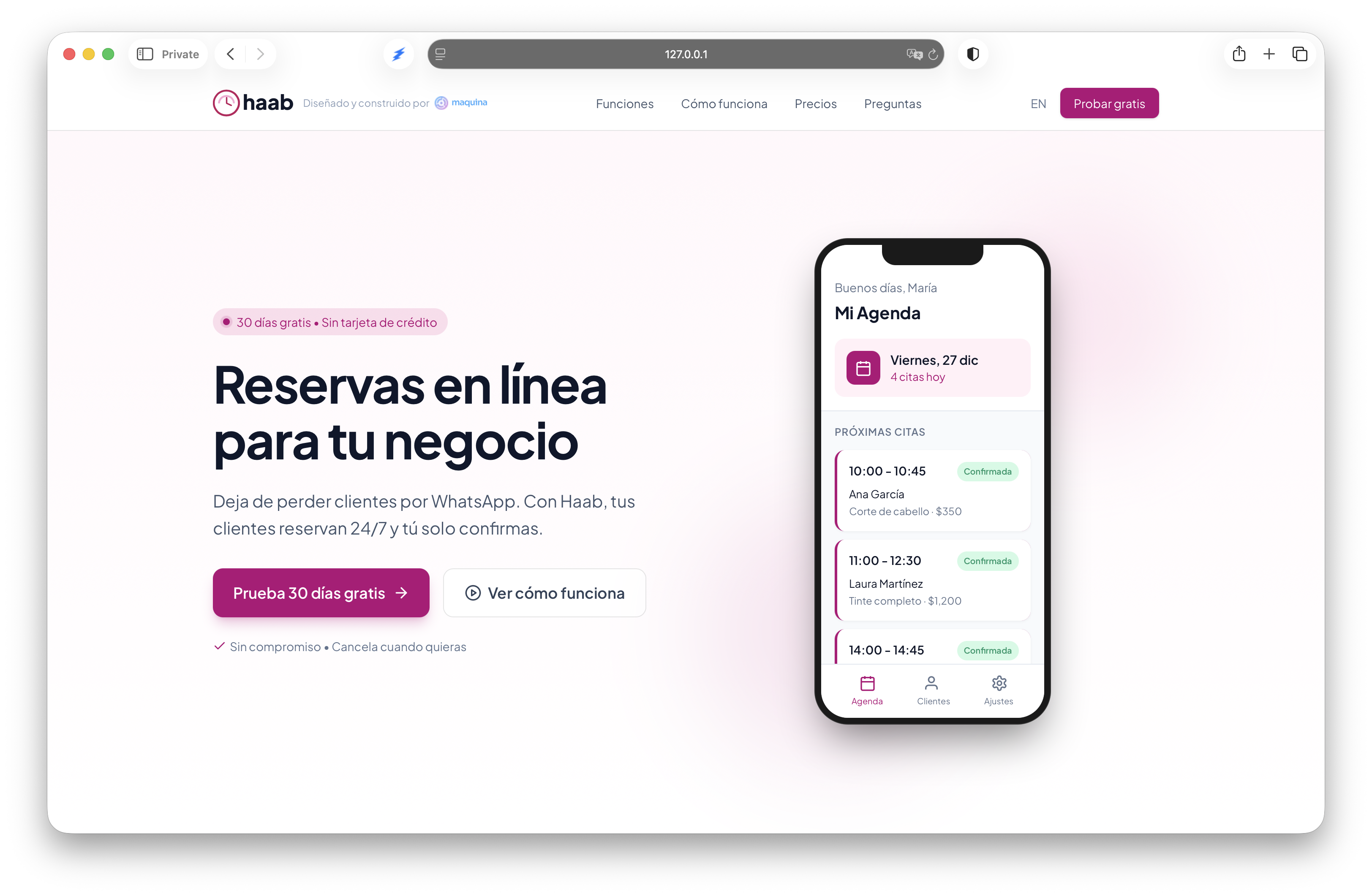

An example: Haab. I started this Rails application a few weeks ago using this flow. It’s almost ready to launch. What would have taken me months of evening and weekend work is approaching production in weeks. Not because AI wrote perfect code, but because the layered documentation kept it generating code I could actually ship.

Conclusion

I still don’t see how AI can replace anyone in software development. It brings the possibility of delivering code faster—way faster than before. But it also reveals something important: being a great communicator matters more than being a fast coder.

All those documents, specs, and guides I described are communication work. The AI does the typing. Your job is to be clear about what you want, provide the right context, and know when to step in. That’s still software development. It’s just a different kind of skill.